Title & author

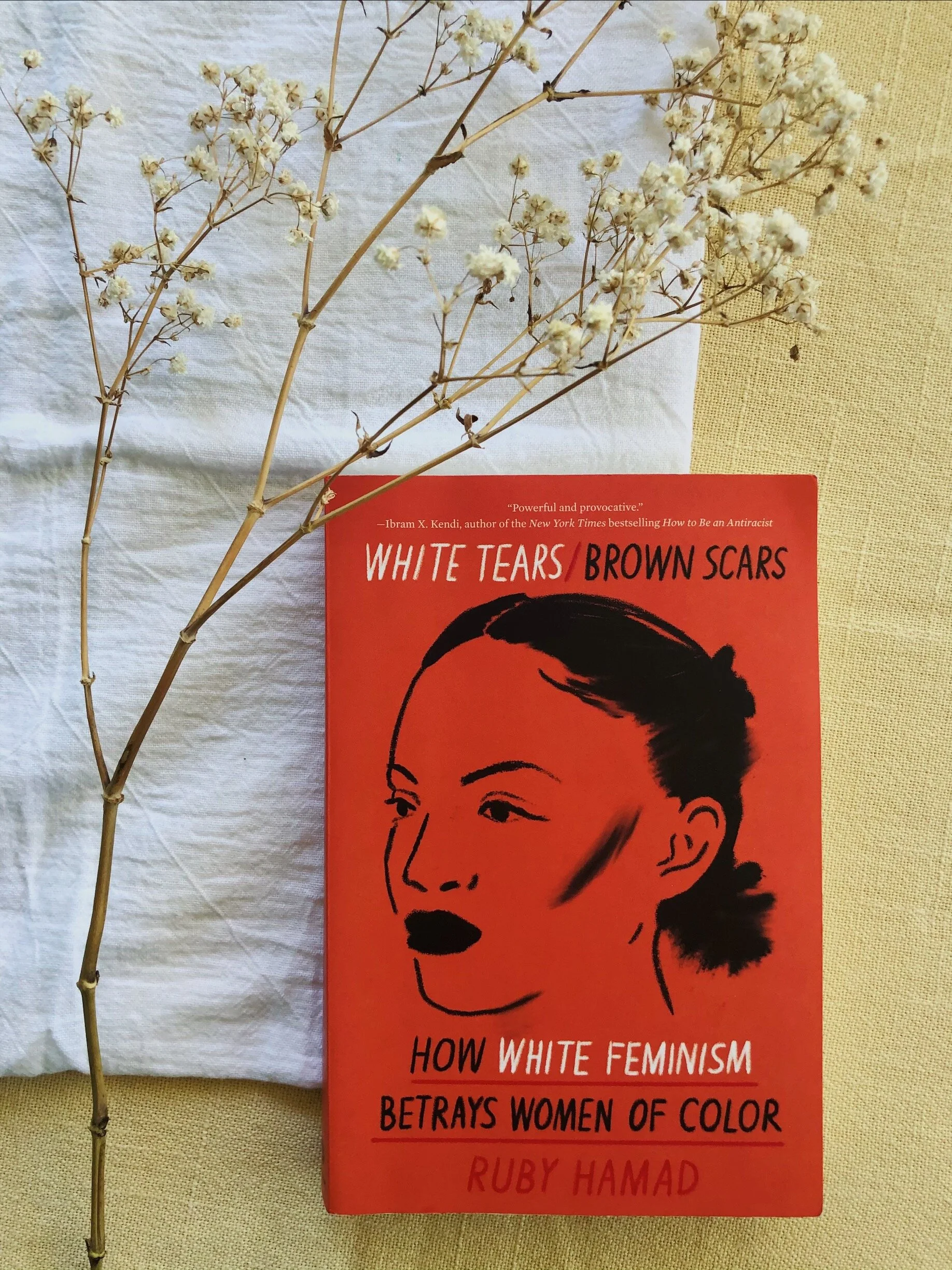

White Tears/Brown Scars: How White Feminism Betrays Women of Color by Ruby Hamad

Synopsis

With its deep dive into the impact of colonialism, imperialism, and white supremacy around the world, Ruby Hamad’s White Tears/Brown Scars: How White Feminism Betrays Women of Color (Catapult, 2020) is a much needed addition to the feminist cannon. Hamad weaves together global examples to demonstrate the negative impact of Westernization on women of color everywhere, particularly through the constructed binary between them and white women, and to call for the destruction of white feminism to end patriarchal control.

Who should read this book

Everyone

What we’re thinking about

How our history classes conveniently forgot to mention any of the examples Hamad weaves throughout the title

Trigger warning(s)

Physical violence, sexual violence, slurs, sexism, racism, Islamophobia

Kimberlé Crenshaw, Mikki Kendall, Audre Lorde, bell hooks– these are just a few critical writers on white feminism and intersectionality. However, in US mainstream media, there aren’t too many reads circulating on white feminism’s global impact. With its deep dive into the impact of colonialism, imperialism, and white supremacy around the world, Ruby Hamad’s White Tears/Brown Scars: How White Feminism Betrays Women of Color (Catapult, 2020) is a much needed addition to this cannon. Hamad weaves together global examples to demonstrate the negative impact of Westernization on women of color everywhere, particularly through the constructed binary between them and white women, and to call for the destruction of white feminism to end patriarchal control.

Diverging from what most individuals are taught in history courses, Hamad utilizes examples of white supremacy’s impact on the Caste systems in India, Indigenous families in Australia, the enslaved in America, Mexicans in Texas during the 1800s, and more, to showcase the construction, implementation, and stronghold of white feminism across the globe. Throughout history, “the West had the power and resources to keep producing reductive representations and pseudo-knowledges of the ‘mysterious’ East until those representations came to seem more real than the real” (Hamad, 35). Hamad draws attention to the well-known concept that ‘winners write history.’ In doing so, she critiques the construction of racism and white people’s creation and reproduction of the “other” in order to justify oppression. Such stereotypes of women of color– such as the “Princess Pocahontas,” the “China Doll,” the “Jezebel,” etc.– were created to enable white colonists’ domination. In creating stereotypical personas, they “affirm[ed] the superiority of white society over [the woman of color’s] own, and so functions as tacit permission for whites to conquer, assimilate, and destroy [their] culture” (37).

But Hamad doesn’t stop there– she then dives into how these depictions of women of color are reinforced by a created binary. “The labeling of black women as ‘easy’ served a double purpose: as well as absolving white men of any shame or wrongdoing by positioning black women as less evolved, animalistic, and ruled by their own carnal desires, it differentiated black women from white women, thereby justifying the sexualization of the former and sexual repression of the latter” (30). These stereotypes and their lingering impact today (for example: how Black women performers are critiqued for their clothing choices; how Asian women are fetishized as schoolgirls; etc) limit both white women and women of color at the hands of white supremacy. Black women– and all women of color– are labeled in ways that serve to ‘justify’ their oppression. And as white women’s image was crafted as the antithesis of Black women’s, white men therefore use that binary to ‘justify’ protecting white women at any cost, upholding their own societal status. Through this created binary, white men, then, become the saviors, the protectors, whatever label they need to explain the actions they take. “Sexism and racism go hand in hand in the West: as long as the myth of the sex-crazed, aggressive, inferior subject races is allowed to fester, then so too will the implication that white women need to be protected from them” (243). As long as women of color are oppressed, argues Hamad, so will white women.

Yet the distance between where we are and where we need to be is vast, with white women continuing to side with white supremacy–and more specifically, the patriarchy–over women of color. Throughout history, white women have attempted to play the role of “the Great White Mother” (141). In Australia, they advocated for the separation of Indigenous children from their families, believing the mothers not to be fit parents, leading to 21,500 Native American children being separated from their families in ten years alone (145). Jenni White, a US columnist and conservative who adopted two daughters from Zambia, claims her daughters are now “Americans. Not African-Americans. Not black girls” (148). In her language is not just white saviorism, but advocacy for assimilation, erasure. Even more, “in 2018, Aboriginal women made up 34 percent of the female prison population in Australia despite Aboriginal people comprising only 2 percent of the overall population” (151). Where are white women here, advocating for the rights of women of color? Rather than advocate for them, “white women navigate the system to keep these racial inequalities entrenched while angling for better status for themselves” (153). A recent real-world example? The pro-Trump rally that resulted in an insurrection–an attempted coup, better yet– at the US Capitol was funded by Women for America First. White women rallied to delegitimize an election based on false claims of voter fraud in a year with historic numbers because of the work and turnout of Black women. They rallied to keep a president in place who has made racist (and violent) comments again and again, at the expense of Black women’s credibility and– even more– their right to vote.

Although many Americans like to claim so, there is no “war on America.” The authors in the canon of intersectional feminism demonstrate how critical it is to America’s democracy that we address our history. And Hamad’s text takes it a step further– it is not just critical for America, but for a just world. After the attack on the Capitol, many took to social media to express that the actions displayed “were not those of America,” but rather those of a “third world country.” White Tears/Brown Scars demonstrates how that is just not true– how, instead, the actions can be seen clearly as a result of white supremacy, a need for white individuals to assert and maintain their control at whatever cost as they have done around the globe again and again, even if it means white women betraying women of color.

“White women have a choice...Will [they] choose to keep upholding white supremacy under the guise of ‘equality’ or will they stand with women of color as we edge ever closer to liberation? ”

Join in

Contribute your thoughts by using the “Leave a comment” button found underneath the share buttons below. Answer one of these questions, ask your own, respond to others, and more.

How did the use of global examples of white feminism deepen your understanding of its problematic nature?

Putting White Tears/Brown Scars in conversation with other feminist titles you’ve read, what action items have you taken away? How have you turned your reading into advocacy?

Please note that all comments must be approved by the moderator before posting. We reserve the right to deny offensive or spam-related commentary. And, for the wellbeing of our BIPOC, LGBTQIA+, and/or disabled-identifying community members, please respect the personal capacity to address questions on certain topics. We encourage you to search for the answer in a great book or online instead. Thank you!